No Really, For Everyone

Creating products accessible to everyone means we need to think how and when people access our products. Hint: it's not always Safari on iOS.

Last week, Rob Brackett tweeted a link to A web for everyone, an article by Jeremy Keith. In that article, Jeremy discusses the need to build products for the web that are accessible to all audiences, not just those with bleeding edge functionality:

I wish we could make offline functionality a requirement. But the reality is that not everyone is using a browser that supports the necessary technology. I wish we could make beautiful typography a requirement. But, again, the reality is that there will always be some browsers or devices that won’t be capable of executing that typography. Accepting these facets of reality might seem like admissions of defeat, but I actually find it quite liberating.

He also links over to The Web isn’t uniform, a terrific article by Karolina Szczur. She writes of he experience when, partly by chance, she ends up browsing the web with Javascript disabled. She punctuates that experience with a timeless reminder:

Ultimately, we’re building for the users, not for our own tastes or preferences.

The broader discussion in both articles is more fundamental than any one technology or technique; it is a discussion about how we (re)adjust our mindset when we sit down to design and build our products.

It is, amongst other things, about the need to be honest with ourselves about our intentions when we build for the web. To be honest about who we are building for, as much as what we are building.

One thing I wanted to add to the discussion came after (briefly) perusing some of the (unfortunately predictable) negative feedback directed at Karolina and her post.

The vast majority of the negative comments focus on defending Javascript as a core technology of the “modern internet.” And that right there is the problem. The modern internet is an extremely varied place.

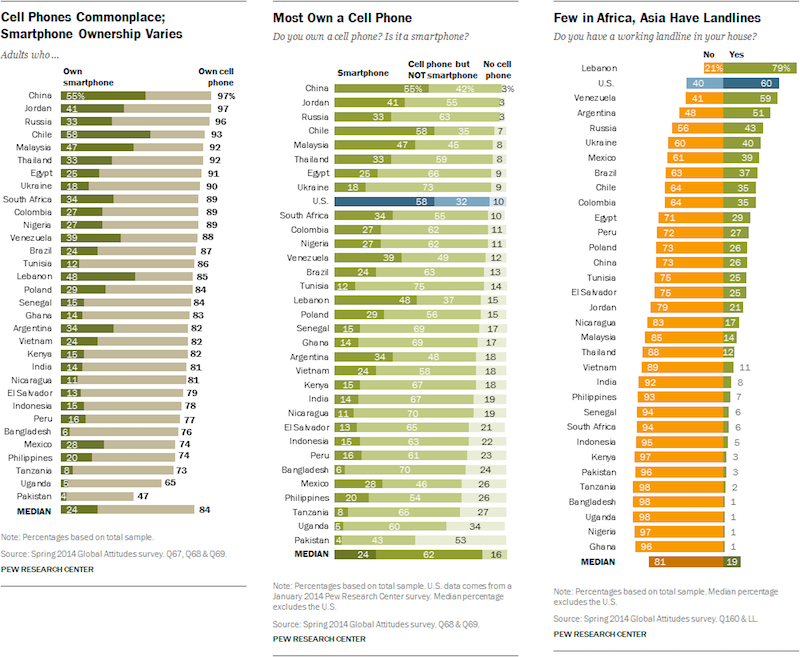

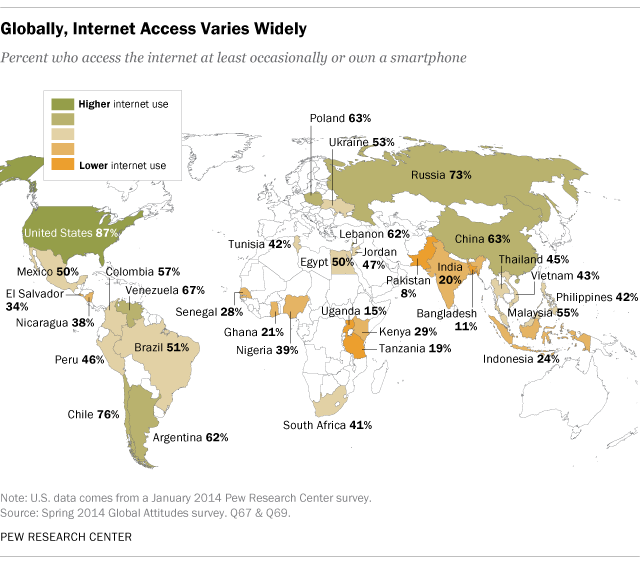

While the data is a bit old, consider these charts from a Pew Research Center report, Communications Technology in Emerging and Developing Nations:

A median of only 24% say they own a cell phone that can access the internet and applications.

Taken together, along with the rest of the article, they suggest that the vast majority of connectivity in emerging markets is over “dumbphones” as opposed to smartphones, tablets or even computers. It is also pretty likely that those users are not on bleeding edge browsers or high speed connections for the most part.

Here’s where I’d like to add to the discussion: We must always advocate for our users, not just when it is convenient.

Over the last few years, bills like SOPA and lots of pro and con legislation about net neutrality have galvanized much of our community in an effort to combat unfair, imbalanced control of internet access. Many of those same voices that are so passionate about Javascript as a cornerstone of the internet have also been ardent defenders of keeping the internet free, open and available to all.

That concern for equal access to the internet requires demands those very same qualities Karolina and Jeremy are advocating: empathy, compassion, love.

If we stand behind equal, unrestricted internet access as something fundamental to our modern environment, then is it not hypocritical to deny access to those who may not be privileged enough to be browsing Facebook in Canary, fullscreen, on their shiny Retina 5K iMac?

Surely, even if the numbers of smartphone users has increased since the Pew survey data was collected, there is still a long way to go in emerging markets, and even many established markets. Again, Pew illustrates the challenges that lie ahead:

These cell phones and smartphones are critical as communication tools in most of the emerging and developing nations, mainly because the infrastructure for landline communications is sparse, and in many instances almost nonexistent. In these emerging and developing nations, only a median of 19% have a working landline telephone in their home. In fact, in many African and Asian countries, landline penetration is in the low single digits.

Think about that last bit for a second. Technologies like Facebook’s Safety Check are great, but (afaik) it requires access to a smartphone app or an internet connection from a browser capable of logging into Facebook (which we have seen from Karolina’s article, requires Javascript).

If there is a natural disaster, wouldn’t it be better if people could simply send SMS to a predetermined number, which would in turn update a web page somewhere for others to check? What if you’re not safe, and you’d like to notify others you need help? Why are private companies outpacing public services and governments when it comes to basic humanitarian services such as this?

None of this is about Javascript. None of this is about CSS transforms or WebGL. None of this is about technology at all.

It is about making products that serve all users equally. It is about putting ourselves in others’ shoes. It is about trying to imagine the frustration and difficulty of using our products when the conditions aren’t what we’re used to. It is about being human.

It goes without saying that I’d also highly recommend reading (several times) the terrific Design For Real Life by Sara Wachter-Boettcher and Eric Meyer. I’ve been meaning to write something about how transformative their book was, for me, but haven’t yet had the courage to tell that story.

Twitter

Google+

Facebook

Reddit

LinkedIn

StumbleUpon

Email